May 2, 2024 — Lots of countries are voting. Recent elections in a number of Emerging Market and Developing Economies (EMDEs) have demonstrated anew the proposition that major currency devaluations are more likely to come immediately after an election, rather than before one. Nigeria, Turkey, Argentina, Egypt, and Indonesia are five countries that have experienced post-election devaluations within the last year.

- The election-devaluation cycle

Economists will recall a 50-year-old paper by Nobel Prize winning professor Bill Nordhaus as essentially initiating research on the Political Business Cycle (PBC). The PBC refers to governments’ general inclination towards fiscal and monetary expansion in the year leading up to an election, in hopes of re-electing the incumbent president or at least the incumbent party. The idea is that growth in output and employment will accelerate before the election, boosting the government’s popularity, whereas the major costs in terms of debt troubles and inflation will come after the election.

But the seminal paper by Nordhaus (1975) also included the prediction of a foreign exchange cycle particularly relevant for EMDEs. That is the proposition that countries generally seek to prop up the value of their currencies before an election, spending down their foreign exchange reserves if necessary, only to undergo a devaluation after the election.

Nordhaus wrote, “It is predicted that the concern with loss of reserves and balance of payments deficits will be greater in the beginning of electoral regimes, and less toward the end.…The basic difficulty in making intertemporal choices in democratic systems is that the implicit weighting function on consumption has positive weight during the electoral period and zero (or small) weights in the future.”

The devaluation may be undertaken deliberately by an incoming government, choosing to get the unpleasant step — with its unpopular exacerbation of inflation — out of the way while it can still blame it on its predecessors. Or the devaluation may take the form of an overwhelming balance-of-payments crisis soon after the election. Either way, a government has an incentive to hoard international reserves during the early part of its term in office, and to spend them more freely to defend the currency toward the end of its term.

A political leader is almost twice as likely to lose office in the six months following a major devaluation as otherwise, especially among presidential democracies. Why are devaluations so unpopular that governments fear to undertake them before elections? In the traditional textbook model, a devaluation stimulates the economy by improving the trade balance. But devaluations are always inflationary. Furthermore, devaluations in EMDEs often are contractionary for economic activity, particularly via the adverse balance sheet effects on those domestic borrowers who had incurred debts denominated in dollars.

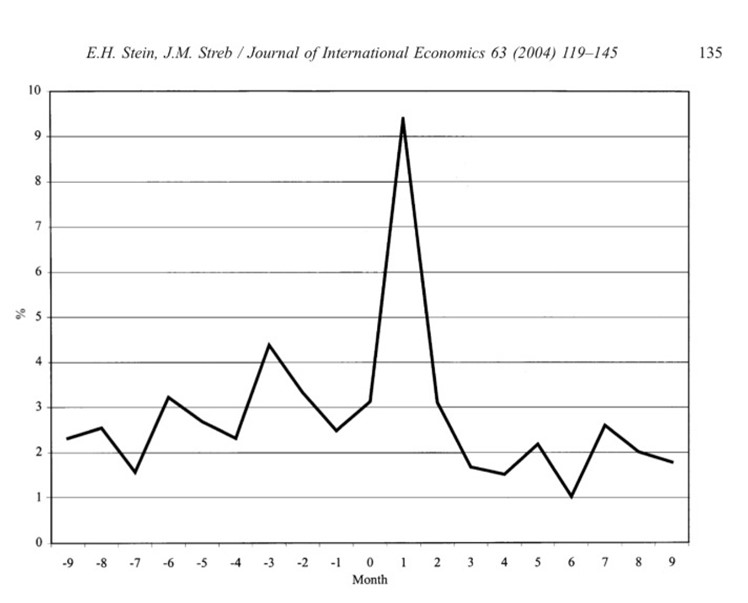

The theory of the political devaluation cycle was developed in a series of papers by Ernesto Stein and co-authors. One might think that voters would wise up to these cycles and vote against a leader who sneakily postponed a needed exchange rate adjustment. But given a lack of information about the true nature of the politicians, voters may in fact be acting rationally. The graph, from Stein and Streb (2005) shows that devaluations are far more common in the immediate aftermath of changes in government. (The sample covers 118 episodes of changes in government, excluding coups, among 26 countries in Latin America and the Caribbean between 1960 and 1994.)[1] Figure: Pattern of average devaluation before and after elections in Latin America.

Figure: Pattern of average devaluation before and after elections in Latin America.

2. Five devaluations over the past year

Many EMDEs have been under balance of payments pressure during the last two years. One factor is that the US Federal Reserve raised interest rates sharply in 2022-23 and is now leaving them higher for longer than markets had been expecting. Consequently, international investors find US treasury bills more attractive and EMDE loans and securities less attractive.

A good example of the political devaluation cycle is Nigeria. Africa’s most populous country held a contentious presidential election on February 25, 2023. The incumbent, who was term-limited, had long used foreign exchange intervention, capital controls, and multiple exchange rates, to avoid devaluing the currency, the naira. The new Nigerian president, Bola Tinabu, was inaugurated on May 29, 2023. Two weeks later, on June 14, the government devalued the naira by 49% [from 465 naira/$, to 760, computed logarithmically]. It soon turned out that this was not enough to restore equilibrium in the balance of payments. At the end of January 2024, the government abandoned its effort to prop up the official value of the naira, devaluing another 45 % [from 900 naira/$ to 1,418, logarithmically].

A second example is Turkey’s election in May 2023. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has long pursued economic growth by obliging the central bank to keep interest rates low — a populist monetary policy that was widely ridiculed because of the President’s insistence that it would reduce soaring inflation — while simultaneously intervening to support the value of the lira. The government guaranteed Turkish bank deposits against depreciation, an expensive and unsustainable way to prolong the currency overvaluation. After the elections, the lira was immediately devalued, as the theory predicts. The currency continued to depreciate during the remainder of the year.

Next, on November 19, 2023, Argentina elected a surprise candidate as president, Javier Milei. Often described as a far-right libertarian, he comes from none of the established political parties. He campaigned on a platform of diminishing sharply the role of the government in the economy and abolishing the ability of the central bank to print money. Milei was sworn in on December 10. Two days later, on December 12, he cut the official value of the peso by more than half [a 78 per cent devaluation, computed logarithmically, from 367 pesos per dollar to 800]. At the same time, he took a chain saw to government spending, such as subsidies to energy, rapidly achieved a budget surplus, and initiated sweeping reforms. Argentine inflation remains very high, but the central bank stopped losing foreign exchange reserves after the devaluation, again as predicted by the theory.

A fourth example is Egypt, where President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi just started a third term, on April 2. The economy has been in crisis for some time. Nevertheless, the government had ensured its overwhelming re-election on December 10-12, 2023, by postponing unpleasant economic measures, not to mention by preventing serious opponents from running. The widely expected devaluation of the Egyptian pound, 45 %, came last month, on March 6, 2024 [from 31 pounds/dollar to 49, logarithmically]. It was part of an enhanced-access IMF program, which also included the usual unpopular monetary and fiscal discipline [with disbursal approved by the IMF Executive Board on March 29].

Finally, in Indonesia, the widely-liked but term-limited President, Jokowi, is soon to be succeeded by the Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto, who is less widely liked but was backed by the incumbent in the February 14 election. The rupiah has been depreciating ever since the March 20 announcement of the outcome of the contentious presidential vote. It fell almost to an all-time record low against the dollar on April 16.

3. What next?

Of course, the association between elections and the exchange rate is not inevitable. India is undergoing elections now and Mexico will in June. But neither seems especially in need of major currency adjustment.

Bolivia is one candidate for the election-devaluation cycle. It is deeply divided politically, over whether former President Evo Morales can run in elections scheduled in 2025. In the meantime, the country is under continuing balance of payments pressure, with international reserves dwindling.

Venezuela is scheduled to hold a presidential election in July. As with some other countries, the election is expected to be a sham, because no major opposition candidates are allowed to run. The economy is in a shambles due to long-time mismanagement, featuring hyperinflation in the recent past and a chronically overvalued bolivar. But the same government that essentially outlaws political opposition also essentially outlaws buying foreign exchange. So, equilibrium may not be restored to the foreign exchange market for a long time.

To stave off devaluation, these countries do more than just spend their foreign exchange reserves. They often use capital controls or multiple exchange rates, as opposed to allowing free financial markets. That doesn’t invalidate the phenomenon of post-election devaluations; it just works to insulate the governments a bit longer from the need to adjust to the reality of macroeconomic fundamentals. Unfortunately, many of these countries also fail to allow free and fair elections, which works to also insulate the government from the need to respond to the voters’ verdict.

References

Broz, J. Lawrence, Maya Duru, and Jeffry Frieden, 2016, “Policy Responses to Balance-of-Payments Crises: The Role of Elections,“ Open Econ Rev, 27, no.2, pp.207–227.

Frankel, Jeffrey, 2005, “Contractionary Currency Crashes in Developing Countries,” IMF Staff Papers. vol. 52, no. 2. NBER Working Paper No. 11508.

Frieden, Jeffry, and Ernesto Stein, 2001, “The political economy of exchange rate policy in Latin America: an analytical overview.” In Jeffrey Frieden and Ernesto Stein, eds. The currency game: exchange rate politics in Latin America, pp. 1-20.

Nordhaus, William, 1975, “The Political Business Cycle,” Rev. of Econ. Studies Volume 42, Issue 2, April 1975, Pages 169–190.

Quinn, Dennis, Thomas Sattler, and Stephen Weymouth, 2023, “Do Exchange Rates Influence Voting? Evidence from Elections and Survey Experiments in Democracies.” International Organization 77, no. 4, 789-823.

Stein, Ernesto, and Jorge Streb, 1998, “Political Stabilization Cycles in High-Inflation Economies,” Journal of Development Economics, 159-180.

Stein, Ernesto, and Jorge Streb. 2004, “Elections and the Timing of Devaluations.” Journal of international Economics 63, no. 1: 119-145.

Stein, Ernesto H., Jorge M. Streb, and Piero Ghezzi, 2005, “Real exchange rate cycles around elections.” Economics & Politics 17, no. 3: 297-330.

Steinberg, David, 2015, Demanding Devaluation: Exchange Rate Politics in the Developing World (Cornell University Press).

[1] Including Frieden and Stein (2001) and Stein and Streb (1998, 2004, 2005). More recently, Quinn, Sattler, and Weymouth (2023) find that voters punish leaders who devalue, in particular, when the currency was already undervalued. Steinberg (2015) finds that they are more likely to welcome a weak currency in countries where the manufacturing sector is powerful.

[A shorter version appeared at Project Syndicate. I thank Sohaib Nasim for research assistance. Comments can be posted at Econbrowser.]