Has Italy Really “Gone Back Into Recession”?

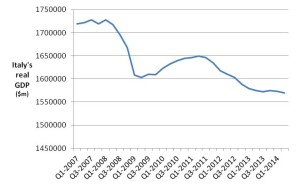

Italians and the world have now been told that their economy slipped back into recession in the first half of 2014. This characterization is based on the criterion for recession that is standard in Europe and most countries: two successive quarters of negative growth. But if the criteria for determining recessions in European countries were similar to those used in the United States, this new downturn would be a continuation of the 2012 recession in Italy, not a new one. A common-sense look at the graph below suggests the same conclusion: the 2013 “recovery” is barely visible.

Worse, Italy under U.S. standards would probably be treated as having been in the same horrific six-year recession ever since the shock of the global financial crisis in 2008: the recovery in 2010-11 was so tepid that the level of Italian economic output had barely risen one-third the way off the floor, before a new downturn set in during 2012. And the two earlier downturns were severe: Italy’s GDP remains 9% below the level of 2008.

Graph of real GDP in Italy, 2007 (Q1) – 2014 (Q2)

What is the difference in criteria? Economists in general define a recession as a period of declining economic activity. European countries, like most, use a simple rule of thumb: a recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of falling GDP. In the United States, the arbiter of when recessions begin and end is the NBER Business Cycle Dating Committee. The Committee does not use that rule of thumb, nor any other quantifiable rule, when it declares the peaks and troughs of the US economy. When it makes its judgments it looks beyond the most recently reported GDP numbers to include a variety other indicators, in part because output measures are subject to errors and revisions.

Furthermore the Committee sees nothing special in the criterion of two consecutive quarters. For example, it generally would say that a recession had taken place if the economy had fallen very sharply in two quarters, even if there had been one intermediate quarter of weak growth in between the other two quarters. Further, if a trough is subsequently followed by several quarters of positive growth the NBER Committee does not necessarily announce that the recession has ended, until the economy has recovered sufficiently well that a hypothetical future downturn would count as a new recession instead of a continuation of the first one.

Fortunately, the US economy has had positive economic growth for the last five years, so these issues are not currently active on our side of the Atlantic. But things are not always so quiet. The US economy contracted three quarters in a row in 2001, for example, measured with the revised GDP statistics that are available today. But at the time when the NBER committee declared that there had been a recession in 2001 (based on various other indicators, particularly employment and the income-based measure of GDP), the official demand-based GDP statistics did not show two consecutive quarters of declining output, let alone three. That episode is a good illustration of the benefits of a broader approach to the task of declaring business cycle turning points. The NBER Committee has never yet found it necessary revise a date, let alone erase a recession, once declared.

One cannot say that the two-quarter rule of thumb used by individual countries in Europe and elsewhere is “wrong.” There are unquestionably big advantages in having an automatic procedure that is simple and transparent, especially if the alternative is delegating the job to a committee of unelected unaccountable ivory-tower economists. The press statements of the NBER Committee are seldom greeted appreciatively. Each time, many critics express puzzlement at the need for a secretive committee, as compared to the alternative of an objective two-quarter rule. (Other critics each time complain that the committee has “only said what everybody has known for a long time.” Some critics have managed both complaints simultaneously — even when the two-quarter rule would not have given this answer that “everybody knows.”)

But there are also disadvantages to the rule of thumb. One disadvantage is the need to get out the white-out when the statistics are revised, as Britain had to do a year ago when its reported recession of 2011-12 was revised away. Claims that in 2012 had appeared in the speeches of UK politicians and in the writings of researchers, made in good faith at the time, were rendered false in 2013.

There is also a potentially more far-reaching and serious disadvantage. Citizens in Italy have now been given the impression that they have entered a new recession. Voters may draw the conclusion that their new political leaders must have done something wrong. But the picture is different if Italy has been in the same recession for six years. The implication may be that the leaders have been doing the same wrong things throughout that period. It’s not an unimportant difference.

The loss in output since 2008 means that the debt/GDP ratio in Italy has risen during this period of fiscal austerity, not reversed as was supposed to happen under the plans to restore debt sustainability. The same is true of other countries in the European periphery, making investor enthusiasm for their bonds over the last two years puzzling.

What are the right policies to get Italy and the others growing again? The answer is the same as it has been for the last six years. At the Frankfurt–Berlin-Brussels level, ease rather than austerity and deflation. At the Rome-Lisbon-Athens level, reforms on the supply side, especially in labor markets. It is true that supply-side reforms take time to have their full effect. But if authorities in Italy started handing out more taxi licenses to (qualified) drivers, employment would go up within a week.